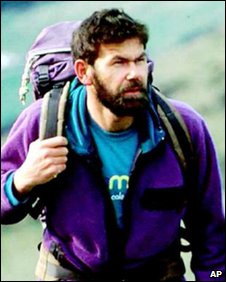

HALL Robert Edwin

Mountaineer

The New Zealand Bravery Star

The New Zealand Bravery Star

Special Honours List 23 October 1999

Special Honours List 23 October 1999

On Friday 10 May 1996, Mr Hall was descending from the summit of Mt Everest, in the Himalayas, following his 11-strong expedition’s attempt on the

On Friday 10 May 1996, Mr Hall was descending from the summit of Mt Everest, in the Himalayas, following his 11-strong expedition’s attempt on the

peak, when a blizzard developed. From the Hillary Step, just below the summit, Mr Hall called on the radio for oxygen and assistance for an American

peak, when a blizzard developed. From the Hillary Step, just below the summit, Mr Hall called on the radio for oxygen and assistance for an American

climber in the party who had collapsed. Other parties on the descent were unable to reascend due to the storm, yet Mr Hall refused entreaties to

climber in the party who had collapsed. Other parties on the descent were unable to reascend due to the storm, yet Mr Hall refused entreaties to

descend without the stricken climber. Fellow New Zealand mountaineer, Mr Andrew Harris, did attempt to reach them, but the American climber died

descend without the stricken climber. Fellow New Zealand mountaineer, Mr Andrew Harris, did attempt to reach them, but the American climber died

during the night. Mr Hall made his way down to the South Summit where early on 11 May he contacted Base Camp by radio. Exhausted and

during the night. Mr Hall made his way down to the South Summit where early on 11 May he contacted Base Camp by radio. Exhausted and

frostbitten, he was unable to descend further. When informed of a failed rescue attempt later that day he responded with dignity and courage. His

frostbitten, he was unable to descend further. When informed of a failed rescue attempt later that day he responded with dignity and courage. His

last communication by radio and satellite link was to give encouragement to his expectant wife in New Zealand. Out of oxygen, he succumbed to the

last communication by radio and satellite link was to give encouragement to his expectant wife in New Zealand. Out of oxygen, he succumbed to the

cold some time during the Saturday night. Mr Hall understood that by remaining behind with the American climber he reduced greatly his own

cold some time during the Saturday night. Mr Hall understood that by remaining behind with the American climber he reduced greatly his own

chances of survival. His selflessness in deciding to remain with him was an outstanding act of bravery.

chances of survival. His selflessness in deciding to remain with him was an outstanding act of bravery.

Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE)

Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE)

Gazetted 11 June 1994, pB34

Gazetted 11 June 1994, pB34

For services to mountaineering.

For services to mountaineering.

KNOWN AWARDS

The New Zealand Bravery Star

Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE)

NOTES

Born 14 January 1961, Christchurch, New Zealand

Died 11 May 1996, Mt Everest, Nepal

BIOGRAPHICAL - Obituary

The New Zealand mountaineer Rob Hall made his last radio call from near the summit of Everest on the evening on 11 May. Crippled by frostbite, running out of oxygen and stranded without food, fluid or shelter, he is presumed to have died that night or the next day. The fact that he died whilst trying to save an exhausted client confirmed his status as the world's most respected leader of commercial Himalayan expeditions.

He was born in Christchurch in 1961, the last of nine children in a Roman Catholic family of modest means. Perhaps because of that background, initiative, enterprise and self- reliance characterised his life from an early age. Living close to the Southern Alps, he discovered mountaineering largely through his own efforts, quickly developing the resilience typical of New Zeal-and's finest climbers. Leaving school at 14, he approached Alpsports with a selection of his own prototypes for rucksacks, tents and outdoor clothing. The company signed him on as designer and by the age of 17 he was in charge of a large team of seamstresses.

He was born in Christchurch in 1961, the last of nine children in a Roman Catholic family of modest means. Perhaps because of that background, initiative, enterprise and self- reliance characterised his life from an early age. Living close to the Southern Alps, he discovered mountaineering largely through his own efforts, quickly developing the resilience typical of New Zeal-and's finest climbers. Leaving school at 14, he approached Alpsports with a selection of his own prototypes for rucksacks, tents and outdoor clothing. The company signed him on as designer and by the age of 17 he was in charge of a large team of seamstresses.

Meanwhile, Hall was also honing his climbing skills and in 1980, still only 19, he reached his first Himalayan summit, the 6,856-metre Ama Dablam in Sola Khumbu - the Sherpa region of Nepal where he would later become so well known and liked. The following year he climbed another Himalayan peak, Numbur (6,954 metres), but it was at home, in the New Zealand Alps, that he really caused a stir, making the first winter ascent, with Steve Lassher, of the Caroline Face of Mt Cook. The altitude here is not extreme, but the scale is vast. It took the pair just eight and a half hours to climb this one-and-a-half-mile-high face, which had taken most previous parties about 22 hours in summer.

Meanwhile, Hall was also honing his climbing skills and in 1980, still only 19, he reached his first Himalayan summit, the 6,856-metre Ama Dablam in Sola Khumbu - the Sherpa region of Nepal where he would later become so well known and liked. The following year he climbed another Himalayan peak, Numbur (6,954 metres), but it was at home, in the New Zealand Alps, that he really caused a stir, making the first winter ascent, with Steve Lassher, of the Caroline Face of Mt Cook. The altitude here is not extreme, but the scale is vast. It took the pair just eight and a half hours to climb this one-and-a-half-mile-high face, which had taken most previous parties about 22 hours in summer.

For three years Hall combined his gear-manufacturing work with summer seasons as a guide and rescue team leader for the New Zealand Antarctic Research Programme. Then in 1987 he returned to the Himalaya, intent on climbing some of the very highest peaks. There were several attempts - on Annapurna, K2 and Everest, mainly with his older climbing partner, Gary Ball - before the two of them finally achieved success on Everest in 1990. They reached the summit with Sir Edmund Hillary's son Peter, broadcasting on the radio, direct from the top of the world to every home in New Zealand.

For three years Hall combined his gear-manufacturing work with summer seasons as a guide and rescue team leader for the New Zealand Antarctic Research Programme. Then in 1987 he returned to the Himalaya, intent on climbing some of the very highest peaks. There were several attempts - on Annapurna, K2 and Everest, mainly with his older climbing partner, Gary Ball - before the two of them finally achieved success on Everest in 1990. They reached the summit with Sir Edmund Hillary's son Peter, broadcasting on the radio, direct from the top of the world to every home in New Zealand.

Capitalising on this hard-earned fame, Hall and Ball immediately put their entrepreneurial skills into raising sponsorship for a global tour to complete all the world's seven highest continental summits in just seven months. They succeeded and became household names in New Zealand, to the extent that they featured, for example, on cereal packet games. Their venture also made a profit (an outcome most climbers dream about but very rarely achieve), which they used to set up an international mountain guiding business, Adventure Consultants.

Capitalising on this hard-earned fame, Hall and Ball immediately put their entrepreneurial skills into raising sponsorship for a global tour to complete all the world's seven highest continental summits in just seven months. They succeeded and became household names in New Zealand, to the extent that they featured, for example, on cereal packet games. Their venture also made a profit (an outcome most climbers dream about but very rarely achieve), which they used to set up an international mountain guiding business, Adventure Consultants.

The very name sounds a contradiction in terms, and to many amateur expeditioners the whole concept of instant, marketable adventure was anathema, but for Hall such purist doubts smacked of elitism: the mountains were for everyone and if clients wanted to pay for expert leadership, he would provide it, complementing Ball's PR skills with his own intuitive business flair. The company quickly built up a base of loyal clients, with a remarkable success rate on the world's most prestigious peaks, particularly Everest. Hall also used the logistics base and the acclimatisation from commercial trips to support his own ambitions; in one 14-month period he reached the summits of five of the world's six highest peaks, concluding with Makalu (8,463 metres) in October 1995. Afterwards he wrote, "Fortune had smiled on me. I gazed across to Everest where we had stood on the south summit just 11 days before. What a fantastic planet we live on and how privileged I am to journey across its mountains."

The very name sounds a contradiction in terms, and to many amateur expeditioners the whole concept of instant, marketable adventure was anathema, but for Hall such purist doubts smacked of elitism: the mountains were for everyone and if clients wanted to pay for expert leadership, he would provide it, complementing Ball's PR skills with his own intuitive business flair. The company quickly built up a base of loyal clients, with a remarkable success rate on the world's most prestigious peaks, particularly Everest. Hall also used the logistics base and the acclimatisation from commercial trips to support his own ambitions; in one 14-month period he reached the summits of five of the world's six highest peaks, concluding with Makalu (8,463 metres) in October 1995. Afterwards he wrote, "Fortune had smiled on me. I gazed across to Everest where we had stood on the south summit just 11 days before. What a fantastic planet we live on and how privileged I am to journey across its mountains."

These words suggest that, for all the commercial hard-headedness, he had not lost a sense of wonder. Nor was he deluded about the risks of high altitude, particularly after Gary Ball died of pulmonary oedema on Dhauligiri in 1993. The tragedy probably influenced his decision to use supplementary oxygen on the highest peaks. Like all the best mountaineers, he knew when to retreat, and he only succeeded on the notoriously risky summit of K2 on his fourth attempt. With clients he was rigorous about timing, hence the decision to turn back from the South Summit of Everest in 1995. On that occasion, despite the good weather and the pleas of clients, he insisted that it was too late in the day to continue safely; he also felt compelled to help the French climber, Chantal Mauduit, who was suffering from cerebral oedema, even though he was not directly responsible for her.

These words suggest that, for all the commercial hard-headedness, he had not lost a sense of wonder. Nor was he deluded about the risks of high altitude, particularly after Gary Ball died of pulmonary oedema on Dhauligiri in 1993. The tragedy probably influenced his decision to use supplementary oxygen on the highest peaks. Like all the best mountaineers, he knew when to retreat, and he only succeeded on the notoriously risky summit of K2 on his fourth attempt. With clients he was rigorous about timing, hence the decision to turn back from the South Summit of Everest in 1995. On that occasion, despite the good weather and the pleas of clients, he insisted that it was too late in the day to continue safely; he also felt compelled to help the French climber, Chantal Mauduit, who was suffering from cerebral oedema, even though he was not directly responsible for her.

As one observer noted of this year's 11 different expeditions on the Nepalese side of Everest, it was to Rob Hall that everyone looked for leadership. Likewise, back in 1987, when a Polish climber was stranded high on the Tibetan side of Everest after an avalanche accident, it was Hall and Ball who took the initiative to hire a truck in Kathmandu, dirve right over the Himalaya into Tibet and rescue the Pole. In the words of an old colleague, Nick Banks, ''Rob was never fazed by obstructive bureaucracy. He always saw the simple solution to a problem and targeted the right person to cut through all the red tape.''

As one observer noted of this year's 11 different expeditions on the Nepalese side of Everest, it was to Rob Hall that everyone looked for leadership. Likewise, back in 1987, when a Polish climber was stranded high on the Tibetan side of Everest after an avalanche accident, it was Hall and Ball who took the initiative to hire a truck in Kathmandu, dirve right over the Himalaya into Tibet and rescue the Pole. In the words of an old colleague, Nick Banks, ''Rob was never fazed by obstructive bureaucracy. He always saw the simple solution to a problem and targeted the right person to cut through all the red tape.''

Last week colleagues and competitors were all acknowledging the meticulous professionalism of Hall's outfit. Contrary to popular misconception, his ''guided'' expeditions were far more competently run than many a traditional amateur venture and his clients were not necessarily tycoons with more money than sense. Douglas Lanson, whose life Hall tried to save last week, was an American Post Office clerk, with 22 years' climbing experience, who had mortgaged himself up to the hilt to pay for his Everest dream. The tragedy was that he died achieving that dream. We shall probably never know exactly how he came to be on the summit so late, only starting to descend at about 3 in the afternoon. Perhaps Hall for once allowed a client's ambition to override his own judgement, but that remains conjecture.

Last week colleagues and competitors were all acknowledging the meticulous professionalism of Hall's outfit. Contrary to popular misconception, his ''guided'' expeditions were far more competently run than many a traditional amateur venture and his clients were not necessarily tycoons with more money than sense. Douglas Lanson, whose life Hall tried to save last week, was an American Post Office clerk, with 22 years' climbing experience, who had mortgaged himself up to the hilt to pay for his Everest dream. The tragedy was that he died achieving that dream. We shall probably never know exactly how he came to be on the summit so late, only starting to descend at about 3 in the afternoon. Perhaps Hall for once allowed a client's ambition to override his own judgement, but that remains conjecture.

Whatever the reason, once it became apparent that Lanson was deteriorating fast in the afternoon blizzard, Hall decided honourably that he must stay with his client. Even when a colleague pleaded with him on the radio to abandon a hopeless case, Hall insisted on remaining with the stricken man, knowing that at nearly 29,000 feet neither of them could survive long. Lanson died that night. The following evening, on 11 May, too weak and frostbitten to move, Hall spoke for the last time on the radio to his wife Jan Arnold in New Zealand. She was seven months pregnant with his child. The poignancy of that farewell was almost unbearable, but there is some consolation in knowing that Jan Arnold had herself climbed Everest with Hall in 1993. She had shared his dreams and she understood the risks. And she knew that, in a situation where "Every man for himself" is the norm, her husband had died trying to save another life.

Whatever the reason, once it became apparent that Lanson was deteriorating fast in the afternoon blizzard, Hall decided honourably that he must stay with his client. Even when a colleague pleaded with him on the radio to abandon a hopeless case, Hall insisted on remaining with the stricken man, knowing that at nearly 29,000 feet neither of them could survive long. Lanson died that night. The following evening, on 11 May, too weak and frostbitten to move, Hall spoke for the last time on the radio to his wife Jan Arnold in New Zealand. She was seven months pregnant with his child. The poignancy of that farewell was almost unbearable, but there is some consolation in knowing that Jan Arnold had herself climbed Everest with Hall in 1993. She had shared his dreams and she understood the risks. And she knew that, in a situation where "Every man for himself" is the norm, her husband had died trying to save another life.

Courtesy - Stephen Venables